As Robin Ince gets a Guardian platform to express his views on experts and windbags, I thought it might be interesting to bring out a piece of work written 9 years ago that’s never really got the traction it deserves (In my opinion. Or expertise. Depending who’s judging me). The fact that it sits firmly behind a paywall even though it’s nearly a decade old is undoubtedly part of the reason.

Robin (can I call him that? Good.) talks about how over-opinionated our society has become and I have a lot of empathy with that. He makes a very good point in that across the internet you can always find someone that shares your view however …err…niche, so you accord a specious validity to whatever might come out of your mouth.

Sadly he then wades into an exploration of expertise without really distinguishing the difference between what he calls “experts” and “so-called experts”. The two things he does draw out are that experts are effective in their practice (the handles don’t fall off your soup mug) and that you can back your opinions up (you can explain *why* you hold a view). Even a cursory glance suggests this is a bit lacking – many of us pontificating on the internet or those on TV are in the business of throwing ideas about rather than making soup bowls, so who judges whether ideas ‘work’? And what if my explanation as to why I hold a view is a scaffold of nonsense too? Not all foundations are firm, regardless of how clearly they are articulated.

I don’t want to pick apart Ince’s piece because I think he raises an important question about the “public intellectual” and the fact that EVERYBODY has an opinion of EVERYTHING and isn’t afraid to share it. I just want to highlight that clever people (Harry Collins for example) have spent many years thinking clearly about what expertise is and what its role is and they’ve generally come up with more substantive ideas than ‘expert’ and ‘windbag’. The irony will not be lost on many of you I’m sure.

A lot of that work though focusses on how expertise plays out in professional environments and in the governance of science. How well does this translate to the “public expert”? Here, I’d like to roll in Peter Healey’s 2004 work on Scientific Connoisseurs and Other Intermediaries: Mavens, Critics and Pundits (£).If you’re interested in science, art, culture, public intellectuals it’s worth a read.

The choice of the old-school word connoisseur is purposeful: Healey is conjuring up ideas of wine connoisseurs and art connoisseurs who have traditionally separated the practice of a thing from the judgement of it – we don’t expect wine and art buffs to be vinyers or artists. We have connoisseurs of tobacco, chocolate and sport. Is it only in relation to science, they ask, that society does not recognise that non-practitioners have a role to play in discriminating between good and poor performance – in acting as connoisseurs?

Connoisseurship however has quite distinct cultural connotations and if you’re anything like me you’ve currently got a mental image of Peter Ustinov in a smoking jacket with a fine claret and a spittoon. Healey was also suspicious of the elitist associations of these traditional understandings of the connoisseur so drew out the maven, the critic and the pundit to offer up more modern, more transferable, more accessible roles:

• The maven has an expertise that is “narrow but deep”, accumulating knowledge on a broad range of aspects of one particular category or subject. This knowledge is not gained from the practice of an expertise and is probably closest to the traditional understanding of the connoisseur. The maven is all about sharing this knowledge and socially is very powerful (see Malcolm Gladwell’s “Tipping Point” for more on this)

• The critic is a practitioner (or ex-practitioner) with expertise and experience who is looking to change the establishment from the inside. Healey looks to Britain’s 1970s movement for social responsibility in science (like Scientists for Global Responsibility, for example). I think much of Ben Goldacre’s Bad Science work quite clearly fits in this category.

• The pundit, in Healey’s typology, possesses less direct knowledge and draws on other people’s opinions. Punditry is not a well-regarded activity and is not adding anything to the debate – its one manifestation of Ince’s windbag.

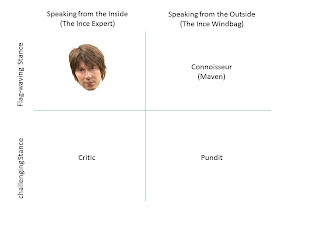

As I went to a business school, I know that all good ideas are improved by putting them into a 2×2 so here is my slightly – but not necessarily – tongue-in-cheek overlaying of Ince and Healey. Let’s call it the HIG (Healey-Ince-Gibbs) Matrix of Publicly Expressed Opinions…it’s bound to catch on with a quality name like that. I’ve considered whether the speaker is operating from a position of personal practical experience in that topic, and whether they are applying a supportive or critical stance ( I’m not completely happy with this axis but let’s not let that get in the way of a good 2 x 2).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

(Image from here)

So, when people express opinions it is right to think about what role they are playing in expressing that particular opinion at that particular time, and it is right to ask how broadly one person (or set of people) can actually legitimately comment as ‘experts’. But instead of a binary idea of experts and windbags, maybe we could make that a bit richer by introducing the connoisseur, the maven, the critic and the pundit.